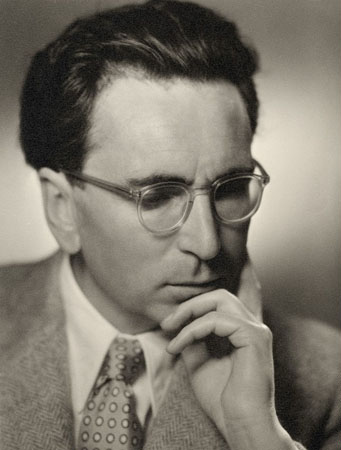

Victor E. Frankl: A Life Well-Lived

“When we are No Longer Able to Change a Situation, we are Challenged to Change Ourselves.” _Victor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Victor E. Frankl was a renowned psychologist in Vienna. When World War II broke out, Frankl was forced into a Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz for his Jewish beliefs. Over the course of three years, Frankl kept navigating between four concentration camps, including Auschwitz, where he had his brother died and his mother murdered. After the war came to an end in 1945, Victor E. Frankl started writing his significant memoir of all times, Man’s Search for Meaning. This landmark book became one of the highly read books all over the world, as it went on to sell over 10 million copies in 24 languages. Despite being permeated with unthinkable cruelties and inhumane atrocities that have always wrung the hearts of its readers, the book has always been a beacon of hope, love, and survival.

In the eyes of the Nazis, Jews were simply valueless. As the memoir narrates, Hitler decided to strip the Jews of every aspect of the humane life: Prisoners were only given a tiny piece of bread and a thin soup to live on throughout their long day of dreary work. The prisoners’ working hours reached 20 hours per day of hard labour in the cold winter days. If a prisoner showed some signs of fatigue, he was beaten to death. Even those who worked conscientiously were sometimes killed for trivial reasons. Surprisingly, despite all the atrocities he witnessed, Frankl not only managed to survive but also modelled a magnificent example for all humanity to look up to in an out-of-balance world. Amid utter wretchedness, Frankl sat down to ponder the most profound concepts of psychology and developed his renowned theory of logotherapy – a theory propounding that the primary motivational force of an individual is to find meaning in life. Frankl’s memoir teaches us that freedom is the ability to choose one’s attitude and mindset, not to live a life devoid of suffering or limitations.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way,” highlights Frankl. Instead of agonizing over the atrocities he went through, Frankl decided to make his days in the concentration camp count; he started using his skills as a trained psychiatrist to help his fellow prisoners by giving them hope and psychological treatment. Frankl mentions that living a life of misery can be a strong catalyst either for embitterment or inspiration. We all feel drained after going through a hard situation, in which we are less appreciated or traumatized, and we even tend to externalise our anger and fear. Frankl urges us to have some second thoughts about this vicious circle of agony because when we keep venting our agony on others, we tend to be sheer copies of those who agonized us in the first place.

The memoir depicts the grandeur of clinging to kindness even in the hardest situations. Frankl showcases how he felt his soul merging into a peaceful state when he decided to share his last loaf of bread with another prisoner. Frankl stopped to tell himself: perhaps this what meaning in life means in the first place! Indeed, the memoir stresses the fact that as humans, we are challenged to create meaning not only find it somewhere. Meaning exists at the present moment, and only you can control it. In the movie Stranger Than Fiction (2013), the same idea is represented when Dustin Hoffman’s character describes meaning as a story that can only be fulfilled when its protagonist performs an action: “Some plots are moved forward by external events and crises. Others are moved forward by the characters themselves. If I go through that door, the plot continues. The story of me through the door. If I stay here the plot can’t move forward, the story ends” explains Hoffman.

When Frankl entered Auschwitz, the manuscript of his memoir was ready for publication, but Nazi soldiers confiscated it from him. Instead of ruminating about such a hurtful experience, Frankl rewrote that manuscript in his head. He kept jotting down virtual notes every now and then, imagining his book read and acclaimed by all Europeans. He dreamt of giving lectures on his biography and his theory of logotherapy to lecture halls full of students in America. Far more than expected, Frankl’s story and therapeutic strategies expanded in ever-widening circles and became known in every part of the globe. Frankl has always been a diehard believer of Nietzsche’s famous quote: “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” Frankl explains that the “why to live” that enabled him to survive was his work, yet he refers to other motives for survival that helped his fellow prisoners, such as love, which evidences itself in a caring attitude towards a family member or even any fellow being. In sum, survival depends on having a purpose that’s bigger than oneself; those who lived only for themselves simply perished.

During the times of war, the world becomes pulled in multiple opposing ways. People are divided into groups and tribes, based on their religion, political beliefs, or ethnicity, yet Frankl attracts our attention to that all-encompassing, divine soul of love that unites all humanity. To exemplify, Frankl was startled to see his victimizers secretly offering him more food, at great risk to their own safety. That is why, Frankl decided to stop limiting his world to guards versus prisoners and to see goodness in everyone he encounters. When he saw those Nazi soldiers venturing out to offer help to the imprisoned Jews, Frankl realized that inside every human being, no matter how cruel he is, there is a divine imprint of love and a rose of benevolence waiting to bud. Frankl teaches us that there are merely two types of people: kind human beings and unkind human beings. The two types exist in every religious and political group, and we all navigate between these two dichotomies. Every human being is a blend of black and white.

Frankl coined the term “Noogenic Neurosis” – the feeling of an inner void. This derives from an inner knowledge of the hollowness caused by a lack of meaning, or an “existential vacuum” – another term coined by Frankl. Frankl lived a life of responsibility by refusing to be a sheer passive reaction to what the world inflicted on him. He often suggested that the ‘Statue of Liberty’ on the East Coast of the United States be accompanied by a ‘Statue of Responsibility’, on the West Coast. Frankl wrote 39 books, which were translated into 49 languages. He was awarded 29 honorary doctoral degrees. Frankl died of a heart failure in 1997, leaving behind a large legacy for all the world to benefit from. He is buried in the Jewish section of the Vienna Central Cemetery. His daughter, Gabriele, decided to follow in his path and became a child psychologist.