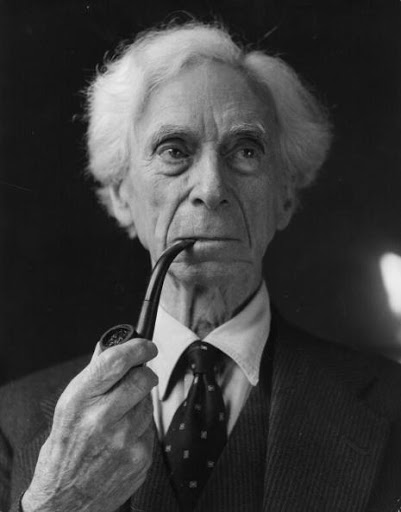

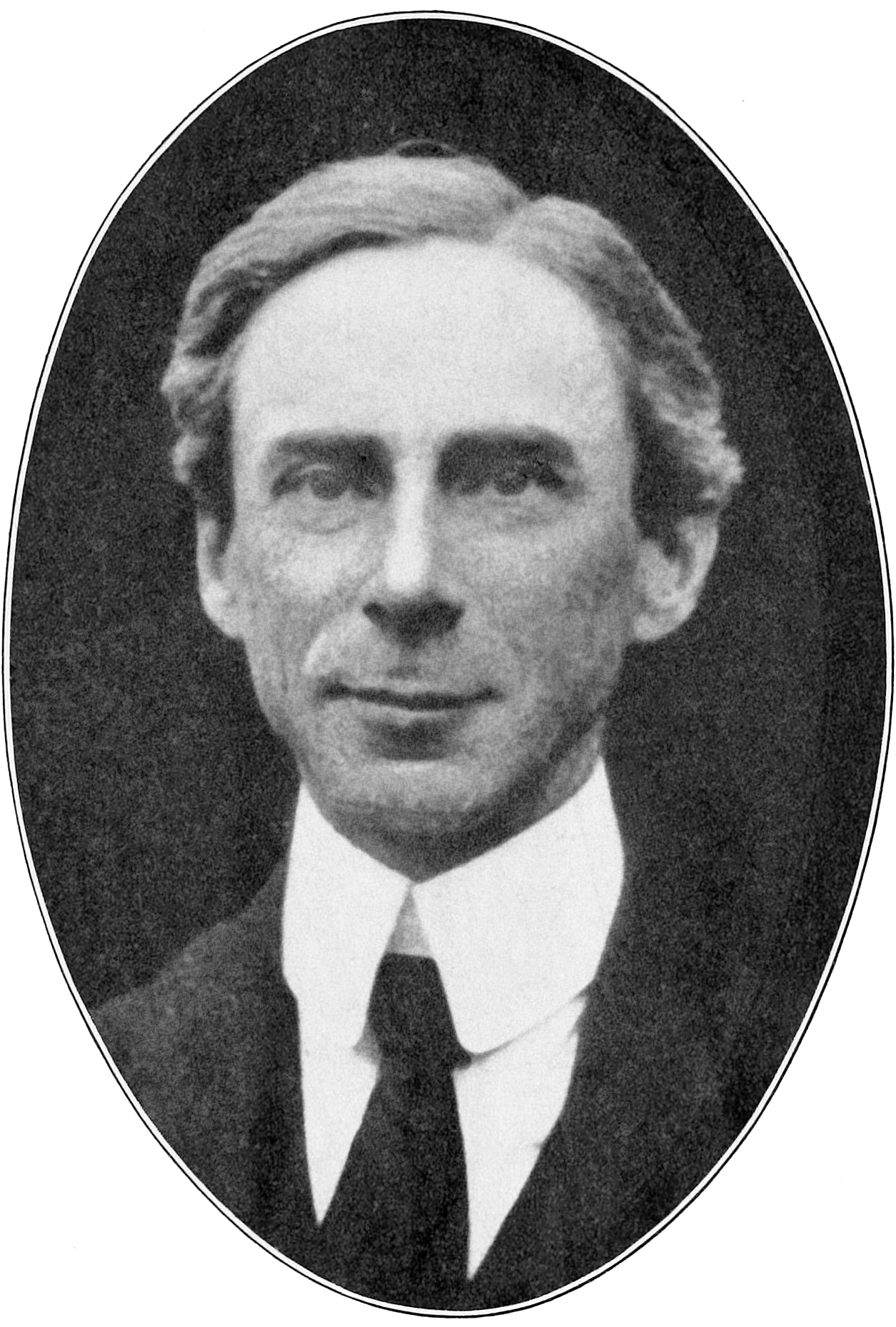

Bertrand Russell: The Philosophy of Idleness

In an environment saturated with economic stimulation, following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, English philosopher, Bertrand Russell chose to praise inactivity! Russel published his landmark essay On Praise of Idleness in 1932, taking the economic world by a storm by arguing that human bliss lies in working less. You might assume that Russell was himself an idle man who lived his life seeking pleasure and luxury, yet he was far from that; Russell was a renowned social activist who published a myriad of essays, which considerably contributed to modern philosophy. Moreover, he established the school of Analytic Philosophy and kept giving back to his society until he died aged 97. So, why indeed did he promote the values of idleness?

The Great Depression that was caused by the Wall Street Crash was the most calamitous economic depression of the 20th century as it wiped out millions of investors. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, the depression lasted for ten years, from 1929 to 1939. Although it took place in The United States, the Great Depression triggered massive deteriorations in output, drastic unemployment, and severe deflation in almost every country of the world. However, according to Russell, the event was an opportunity to revise the economic paradigm of capitalism and critique the work ethics of the time. Russell argues that the economic crisis of his time was itself due to people’s mistaken ideas about work. When people presume that working day and night will contribute to amassing a considerable wealth, it turns out to be the other way round. Russell regards this attitude towards work as a “superficial attitude” since work is “not good” in itself.

Russell begins his essay by explicating the true definition of work to showcase how people’s irrational concepts lead to misery and chaos. So, what is work in the first place? Russell tells us in his essay that there are two types of work – the labourer and the supervisor. The labourer type is about “altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relative to other such matter.” The supervisor type is about “telling other people to alter the position of matter relative to other such matter.” Russell elaborates that the first type is tiresome, boring, and badly paid, whereas the second type is much more paid although it is not of similar difficulty. As we can see the second type can be ever extended, for institutions employ people to supervise not only labourers but also to supervise the supervisors of those labourers. Although Russell was not an advocate of Marxism, he decided to champion the views of Marx regarding the unfair clash between the upper-class society and the lower-class one.

Russell wonders why people value intellectual work (the supervisor type) more than manual work (the labourer type), indicating that this hierarchy of esteem is irrational. Moreover, since the supervisor type is inherently valuable, labourers tend to despise what they do. So, imagine if you spend half of your day doing something that you subconsciously hate, what disastrous results can occur. Moreover, the intrinsic value that work has acquired leads people to despise spare time as a deadly sin; many people nowadays loathe the idle hours of afternoon naps and games, preferring to get engaged in some arduous task. Accordingly, people keep working day and night in a vicious circle, which becomes so jarring to their nervous system. In return, overstimulation takes a great toll on the quality of the work produced. “Immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous,” says Russell.

Since half of the population is prospering in work at the expense of their social life and health while the other half is completely unemployed and miserable, Russell argues that the problem will be solved when working hours are reduced to four hours only per day. Since society is saturated with overworked and unemployed, Russell indicates that by reducing working hours, every society member will have a job and at the same time enjoy other leisure activities. Therefore, in a time permeated with economic pressure, Russell urges his readers to take a no-guilt refreshing nap and even to “play”. Yes, no matter how old you are, it is still your birth-right to play. Russell’s essay has a good take on the significance of playing as it regards people who take pride in being workaholic as not fully alive. Russell even argues that by allowing work to prevail in every minute of our day, we tend to lose our creativity and intellectual skills over time!

You might think that Russel’s viewpoint regarding losing one’s intellectual skills due to overwork is nonsense; you might say that you acquire a valuable, intellectual position as an architect, a doctor, a writer, or a teacher, so it is most unlikely that work dissipates your creativity. Well, if you think about what you do, you will find that your speciality is just a drop in the ocean, compared to all things that you can do in life. As shocking as it might sound, Russell mentions that if you can do nothing apart from the job position you occupy, “it is a condemnation of our civilization.” Moreover, taking playfulness seriously contributes to a highly esteemed view of education and art: Art will be for pleasure’s sake, not for the sake of competition to cater for life’s economic stress and expectations. People will no longer need wars because why on earth would we wage wars and compromise our leisure?!

“Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this, we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever,” remarks Russell. We currently live in a world, saturated with work addiction. To exemplify, in India, employees tend to follow a 5-day, 8- to 9-hour per day working schedule. In Japan, a 2016 government survey found that over 25% of all Japanese companies demand 80 hours of overtime each month, which has negatively affected people’s well-being and increased mortality rate. So, in such a miserable world where liveability is eclipsed by labour, it is recommended that we revise our work principles and views. We are all required to stop giving work free rein to encroach on our social and mental life. Russel’s essay is propaganda for the balanced, meaningful life we all aspire to live despite being impeded by our irrational beliefs and societal standards.

“One of the symptoms of an approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one’s work is terribly important.”

_Bertrand Russell